Decision on Examination of Request for Invalidation (No. 58530)

In one of China’s Top 10 Patent Re-examination / Invalidation cases of 2022, an invalidation decision on a patent claiming Hepatitis B Virus (HBV) RNAi compositions (No. 58530) by the Patent Re-examination Board (the “Board”) sheds light on the standard for post filing data for rejections against sufficiency and inventive step, issues often faced in the biopharmaceutical field, particularly with regards to inventions with sequence listings. This case, between Alnylam Pharmaceuticals Inc. (the “Patentee”) and Zhang Yuan (the “Petitioner”), also marks the first-ever invalidation decision in China for a patent related to RNAi.

RNAi has been gaining traction in the pharmaceutical industry, with the first FDA-approved RNAi agent emerging as recently as 2018. In China alone, around 400 RNAi agents are currently under extensive research. This case marks the first-ever invalidation decision in China for a patent related to RNAi.

The patent in question, CN 108064294, claims a double-stranded RNAi with sense and antisense strands each comprising a specific sequence.

During the proceeding, several key questions pertaining to the patent’s validity were examined.

1. Is there a Lack of Support?

The petitioner raised concerns regarding lack of sufficient support for the patent claims, arguing that the claims’ scopes were excessively broad.

Specifically, they contended that the open-ended term “comprising” in the claims allowed for the addition of any nucleotides to either end of the sequences, resulting in an unknown number and unclear scope of final claimed sequences. However, the CNIPA dismissed these concerns, emphasizing that those skilled in the art would recognize that the silencing effect of siRNA predominantly relied on the primary sequence. They would know how to selectively add nucleotides to enhance the overall sequence’s properties without compromising the bioactivity of the primary sequence. The scope of the claims could be reasonably realized (without undue experimentation) by one skilled in the art.

2. Is there a Lack of Inventiveness?

The petitioner further argued the patented sequences lacked inventiveness because they merely entailed minor modifications from a known HBV iRNA sequence.

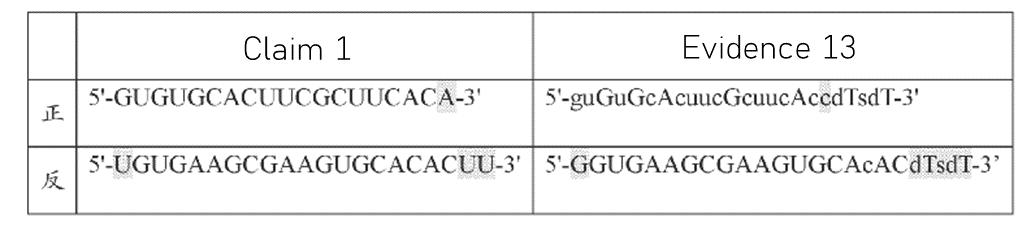

The petitioner presented evidence suggesting that these modifications were common adjustments made to enhance the efficiency of an RNAi sequence. See Figure 1.

The Board disagreed. The Board maintained that due to the inherent unpredictability of the RNAi field, one skilled in the art would recognize that even minor modifications to an RNAi primary sequence could significantly impact the resulting siRNA’s characteristics, including its gene silencing ability against a specific target sequence. After all, the secondary evidence presented only the general rules, not rules specifically on how to modify an HBV RNAi sequence. In addition, the Board noted the presence of conflicts among these general “rules,” particularly among the provided evidence.

Ultimately, the Board upheld the validity of the patent in question.

EIP Thoughts

This case raises an important question: how to determine whether a “difference” between an invention and the prior art is “reasonably expected” (aka, obvious) or not (aka, surprisingly inventive)?

This question carries implications for two key aspects of patentability: sufficiency and inventiveness.

In this case, the petitioner challenged the sufficiency of the patent by arguing that adding nucleotides to the ends of the RNAi sequence would affect the properties of the resulting sequence. Meanwhile, they contested the inventiveness of the patent, arguing that the “minor” nucleotide changes to the primary sequence were taught (or at least implied) by the general teachings in the prior art. In essence, the petitioner seemed to be taking two opposing positions on the same patent during this invalidation challenge. Do small changes to the RNAi primary sequence impact the properties of the sequence or not?

The Board addressed these issues by considering two crucial factors: the state of the art and the problem to be solved.

The Problem to Be Solved

The Board identified the “problem to be solved” to be “providing RNAi agents that inhibit the expression of HBV virus sequences.”

In this case, the focus was on whether the changes were made on the primary (“active”) sequence, which could affect the complementarity to HBV virus sequences and thus the gene silencing abilities against HBV. With respect to sufficiency, the Board concluded that as long as the primary sequence was intact, one of skilled in the art would expect that adding additional nucleotides to each end would have minimal impact on the key function, namely its ability to silence the HBV gene. In other words, the invention would still “work” and the technical problem would still be solved even with the extra nucleotides. If there is sufficient motivation for those skilled in the art to make such changes, even in an unpredictable field, such changes may be deemed readily recognized by a skilled artisan, i.e. obvious.

Inventive Step

With respect to inventiveness, however, a skilled person in the art would expect that a change to the primary sequence would have an effect on the sequence’s complementarity to the target sequence and thus its silencing property. These changes could have an unpredictable, and possibly drastic impact on the sequence’s gene-silencing property. Therefore, even if changes to the primary sequence are implied by general rules, a skilled person would not be motivated to implement those changes.

In other words, it comes down to whether there is motivation for a skilled person to make such changes. Whether there is motivation or not is very case-specific and really depends on (1) the teachings of the prior art and (2) whether such teachings would motivate one of skill in the art to “readily recognize” how a (minor) change could solve the problem (HBV silencing). Unfortunately, it is still easy for Examiners to use hindsight to argue that certain changes are obvious if the results are consistent with prior art teachings, even if the RNAi field as a whole is considered unpredictable.

In this case, the Board concluded that identifying the primary sequence is inventive because it’s hard to predict which sequence will have activity. However, once the primary sequence is identified, the Board thought that minor modifications that kept the primary sequence intact were expected to also solve the technical problem.

In conclusion, this case highlights the complex considerations involved in determining the patentability of emerging biotech technologies and the interplay between prior art, inventiveness, and sufficient disclosure. The nature of the RNAi field is constantly evolving, and Boards may interpret motivation differently depending on numerous factors.

Can We Get Broader Sequence Claims Now?

Although this case looks promising in that it implies applicants can obtain broader claim scopes without providing as much supporting data (e.g., being able to use “comprising” language), our experience with the CNIPA is not consistent with this decision. In a majority of our prosecution cases, Examiners are still very, very reluctant to grant “comprising” language for sequence listings when there is no data support. This is despite the fact that there have been other Top 10 cases[1] that also permitted the use of the term “comprising.”

Still, since Top 10 Cases are usually chosen because they reflect model cases on which others should follow, we hope Examiners and judges alike will take into consideration this case[2], and hopefully we’ll see a shift in the breadth of sequence-listing claim scopes being allowed from the CNIPA.

This Top 10 decision provides valuable guidance for evaluating patentability in emerging technologies and serves as a model case for future cases in the field of RNAi and similar innovative technologies to follow. It emphasizes the importance of considering the specific problem being addressed and the unpredictable nature of certain fields when assessing inventiveness and sufficient disclosure.

If you would like to have more information on this matter or would like to have our advice, please feel free to contact us at eip@eipgroup.asia.

Eagle IP is a top-tier boutique patent firm with a unique mix of experienced US and Chinese patent professionals with significant cross-border knowledge and experience. Our technically expertise covers wide range of technologies including, but not limited, to life sciences, biotechnology, medicine, pharmaceuticals, material and environmental science, chemistry and consumer electronics. We have years of experiences in drafting and prosecuting patent applications involving biological deposits, sequence listings, small and large molecules, drug discovery and development, material science, software and engineering, and many others.

This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice or a legal opinion on a specific set of facts.

-

A top 10 SPC IP court case in the year of 2016 ((2016)最高法行再85号判决) established that using the transitional phrase “comprising” in a sequence claim is permissible and deemed to have adequate support if the claim is further constrained by three factors: 1) the functional limitation of the sequence, 2) the origin of the sequence (e.g., species), and 3) the specific sequence itself. ↑

-

In China, a civil law system, court decisions do not have binding precedential authority. However, they can certainly be influential. ↑

About the Authors

Bonnie Lau is a US Patent Agent at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

Yolanda Wang is a Principal, Chinese Patent Attorney, and Chinese Patent Litigator at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

Jennifer Che, J.D. is Managing Director and a US Patent Attorney at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.