Each year, China’s Supreme People’s Court (SPC) issues its annual “Judgment Digests”, which includes a list of “48 typical cases” highlighting representative SPC decisions in the previous year. The Judgment Digests help us understand more about the SPC’s judicial ideology, trial concepts, and adjudication methods in dealing with difficult and sophisticated legal issues as well as new types of IP cases in high tech fields. Despite the fact that SPC judgments are not precedentially binding on lower courts, they are still very persuasive and provide insights into the types of decisions that are considered “model decisions” by the SPC.

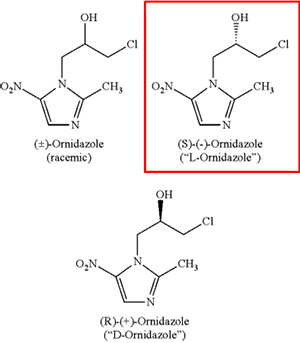

This case was one of the 48 “typical” cases and deals with the standards for inventiveness step of a new drug enantiomer (a single “mirror image” of a molecule) over its racemate “mixture” counterpart.

Background

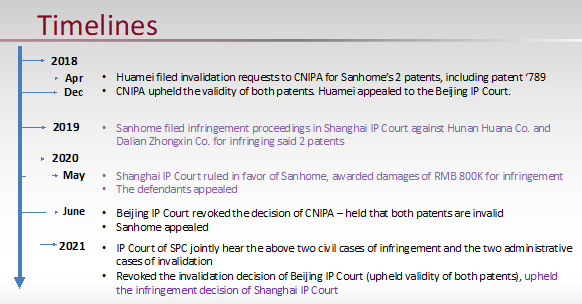

This is a case between two Chinese companies: Patentee Sanhome Pharmaceutical Limited Company 南京圣和公司 (Sanhome) and Petitioner Changsha Huamei Pharmaceutical Technology Company Ltd 长沙市华美医药科技有限公司 (“Huamei”) and revolves around two patents[1] for the use of L-ornidazole in treating anaerobic bacterial and parasitic infections.

Huamei filed invalidation requests to CNIPA for Sanhome’s 2 patents for lack of inventiveness primarily focusing on whether the use of L-ornidazole over its racemate counterpart – which combines L- and D-ornidazole – exhibited unexpected technical effects.

The Patent at Issue

Patent ZL200510068478.9 claimed[2] the single enantiomer L-ornidazole for anti-anaerobic bacterial infection.

In the specification, the patent outlined the problem to be solved, stating “anti-anaerobic bacteria activity of ornidazole has been widely reported in clinical practice … but there are also some adverse effects, primarily expressed as central inhibitory effects. In China, there is a patent application (CN 1400312A) about the separation of racemic ornidazole into L- and D-ornidazole by means of enzymatic resolution, however, comparative studies on the pharmacology and pharmacodynamics between L- and D-ornidazole with racemic ornidazole have not been published yet.”

The patent focused on the surprising activity of the L enantiomer of ornidazole, stating “L-ornidazole is found to have pharmacokinetics characteristics that are superior to D-ornidazole and racemic ornidazole, and also central nervous system toxicity that is lower than D-ornidazole and racemic ornidazole. For these reasons, it would be more practical to formulate L-ornidazole as an anti-anaerobic bacteria infection drug for clinical use.”

The specification provided a large amount of experimental data and embodiments to support the above technical effects.

Key Arguments and Evidence

The Petitioner argued that the claims lacked inventiveness because existing evidence already demonstrated that racemic ornidazole (a mixture of L- and D- ornidazole) had strong inhibitory and killing effects on most anaerobic bacteria. The Petitioner also provided general teaching in the art that disclosed using lipase-catalyzed resolution of ornidazole to obtain “optically pure ornidazole with high enantiomeric excess values” (i.e. pure enantiomer) and hypothesized that if the active enantiomer of the racemic compound can be used, “the required dose can be halved”. For all these reasons, the Petitioner argued that the invention had already been taught in the prior art and thus the patent did not satisfy the inventiveness requirement.

The patent holder countered by presenting extensive experimental data showing that L-ornidazole not only maintained its therapeutic effect but also significantly reduced adverse reactions compared to its racemic mixture, an assertion supported by detailed pharmacokinetics and toxicity data.

CNIPA and Beijing IP Court Decisions

The CNIPA upheld the validity of the patent, stating that the claims were inventive over the prior art because the prior art did not solve the technical problem of (1) treating anti-anaerobic bacterial infections (2) reducing central nervous system toxicity and (3) being safer to use, while the claimed enantiomer had all of these characteristics.

The Beijing IP Court (first instance) disagreed, ruling that the patent lacked inventiveness. The Court framed the technical problem differently, arguing the problem to be solved was use of enantiomer of ornidazole as an alternative to racemic ornidazole for antimicrobial applications. Using this line of reasoning, the Court concluded that the prior art had already disclosed L-ornidazole, and those skilled in the art would be motivated to study the properties of ornidazole enantiomers, and thus find that a certain enantiomer had higher activity and/or lower toxicity as the inevitable result of the research, leading to a conclusion that there is no unexpected technical effect.

Supreme People’s Court Judgment

On appeal, the Supreme People’s Court (“SPC”) criticized the Beijing IP Court for not adhering to the three-step approach for evaluating inventiveness, which includes

(1) determining the closest prior art;

(2) determining the distinguishing features of the invention and the actual technical problem solved; and

(3) determining whether the claimed invention is obvious to a person skilled in the art.

Specifically, for step (3), SPC held that the Beijing IP Court failed to consider whether the prior art as a whole provides technical inspiration to achieve the claimed invention.

Upon reviewing the evidence, the SPC determined that the problem to be solved was to provide a use of a compound for treating anti-anaerobic infection that reduces the toxicity (central toxicity) of racemic ornidazole and is safer to use.

The SPC found that the prior art did not provide any technical inspiration for reducing toxicity or for the specific use of L-ornidazole as a solo treatment for anaerobic bacterial infections.

The prior art only provided guidance on obtaining chiral enantiomers of ornidazole and detecting their biological activity, but did not disclose any activity data for ornidazole enantiomers and the toxicity of ornidazole, nor did it mention using L-ornidazole alone to treat anaerobic bacterial infections. Importantly, it did not suggest any difference in activity between the two enantiomers and thus those skilled in the art could not reasonably predict the biological activity or toxicity of the separated L-ornidazole (as compared to the D-ornidazole).

Moreover, the court underscored the lack of “reasonable expectation of success” in the prior art for the technical effects claimed by the patent. The SPC further clarified that there was no expectation of success if the pharmaceutical use or effect could not be easily inferred or predicted from the structure, composition, molecular weight, known physical and chemical properties, and existing uses of the compound itself, but instead utilizes the newly discovered properties of the compound and produces beneficial technical effects beyond the reasonable expectations of those skilled in the art.

The Court concluded that the closest prior art (a review article that mentioned ornidazole’s neurotoxicity issue as a “temporary phenomenon” and that “ornidazole is relatively safe at normal doses”) was not sufficient to motivate a person skilled in the art to improve the existing technology and further reduce the toxicity of ornidazole.

The SPC emphasized that invention patents in the pharmaceutical field often stem from uncovering new properties of known compounds that are not readily inferable from the existing knowledge base.

Decision

The SPC ultimately upheld all claims of the patent, reinforcing that when a known compound exhibits unexpected properties – in this case, the significantly lower toxicity of L-ornidazole – the inventiveness criteria is met.

“Given the huge number of existing compounds and the large differences in activity/toxicity, very few compounds end up as drugs, and those skilled in the art usually do not have the motivation to conduct relevant studies on a compound and its enantiomers in the absence of specific and clear guidance…If the prior art only provides general research directions in this field or there are conflicting technical teachings, and there is no clear and specific technical inspiration regarding the research of toxicity of chiral enantiomers, it is easy to have hindsight bias and underestimate the inventiveness of the invention by simply determining that the prior art has corresponding technical inspirations.”

This decision underscores the importance of a detailed disclosure of the technical problem and associated effects in the patent specification for supporting the inventiveness of a therapeutic that – on its face – looks similar to the prior art.

Thoughts

For those in the pharmaceutical field, this case brings some clarity to the standard by which inventive step is judged for second medical uses of old compounds as well as for improved isomers, enantiomers, and the like over their racemates. The SPC seems to strongly believe that the pharmaceutical space is indeed an unpredictable art. For example, even prior art which merely predicts research outcomes in general without specific evidence did not destroy the inventiveness of a close enantiomer.

Therefore, even if a molecule is very similar to one in the prior art, as long as the art as a whole does not teach that the differing features are linked to a particular surprising effect (to solve the technical problem), and the patent provides such surprising effect beyond the reasonable expectations of those skilled in the art, the molecule is likely to be considered inventive and patentable.

The SPC’s decision highlights the importance of establishing a clear technical problem and providing strong evidence linking the differences from the prior art to the unexpected technical effects in the patent specification.

If you would like to have more information on this matter or would like to have our advice, please feel free to contact us at eip@eipgroup.asia.

Eagle IP is a top-tier boutique patent firm with a unique mix of experienced US and Chinese patent professionals with significant cross-border knowledge and experience. Our technically expertise covers wide range of technologies including, but not limited, to life sciences, biotechnology, medicine, pharmaceuticals, material and environmental science, chemistry and consumer electronics. We have years of experiences in drafting and prosecuting patent applications involving biological deposits, sequence listings, small and large molecules, drug discovery and development, material science, software and engineering, and many others.

This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice or a legal opinion on a specific set of facts.

-

ZL200510068478.9 – Use of L-ornidazole in the manufacture of medicament for anti-anaerobic bacterial infection 左旋奥硝唑在制备抗厌氧菌感染药物的应用 (patent ‘789) and ZL200510083517.2 – Use of L-ornidazole in the manufacture of medicament for antiparasitic infection 左旋奥硝唑在制备抗寄生虫感染的药物中的应用 (patent ‘517) ↑

-

Claims

1. Use of L-ornidazole in the manufacture of medicament for anti-anaerobic bacterial infection.1. 左旋奥硝唑在制备抗厌氧菌感染药物中的用途。

7. A pharmaceutical preparation for anti-anaerobic bacterial infection, mainly comprising L-ornidazole as an active ingredient.7. 一种抗厌氧菌感染药物制剂,其中主要含有左旋奥硝唑作为活性成分。 ↑

About the Authors

Eddie Ho is a Senior Associate and Chinese Patent Attorney at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

Jennifer Che, J.D. is Managing Director and a US Patent Attorney at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.