The development of China’s approach to patents, especially those in the pharmaceutical and biotech space, has been fascinating to watch. Those of us who have practiced in the area for a long time have been frustrated by the Chinese patent office’s overly strict rules regarding patentability (e.g., high data support standard and refusal to consider post-filing data), while at the same time being more lax on enforcement.

Things have changed a lot in the past five years as China has revamped its patent system in numerous ways. The creation of an entirely new IP court system, the introduction of a new patent law (only the 4th revision in its 40+ year history), the first phase of the US China Economic and Trade Agreement, and recent case law all point in the direction that China is moving rapidly towards upgrading its entire IP infrastructure to be in line with global standards.

The summary of China’s Top 10 Patent Re-Examination and Invalidation Cases of 2020 has just been released and there are two cases in the area of life science. Today, we will discuss an invalidation request of a patent covering Bayer’s small molecule Rivaroxaban, a widely used anticoagulant drug that treats and prevents various conditions that involve blood clots. It was the first orally available direct factor Xa inhibitor and has a global market size of close to $7B USD. The drug was first approved in Europe and the US in 2011, and later in China in 2015.

|

Case number |

4W109873 |

|

Decision day |

August 21, 2020 |

|

Invention Title |

Substituted oxazolidinones and their use in the field of blood coagulation |

|

Invalidation Petitioner |

南京正大天晴制药有限公司 Nanjing Zhengda Tianqing Pharmaceutical Company |

|

Patentee |

拜耳知识产权有限责任公司 Bayer Intellectual Property GmbH |

|

Patent No. |

00818966.8 |

|

Application date |

December 11, 2000 |

|

Earliest Priority Date |

December 24, 1999 |

|

Grant Date |

July 05, 2006 |

|

Invalidation Request Date |

December 13, 2019 |

|

Legal basis |

Article 26, paragraphs 3 (sufficiency/enablement) and 4 (clarity of scope) of the Patent Law, Article 22, paragraph 3 (inventiveness) of the Patent Law + Article 29 (priority claiming validity) |

Quick Summary of the Case

Background:

In 2019, Nanjing Chia Tai Tianqing Pharmaceutical Company became the first domestic (Chinese) manufacturer to obtain approval as a qualified generic manufacturer for “Rivaroxaban Tablets”. The original Rivaroxaban compound patent expired at the end of 2020. However, Bayer’s numerous infringement suits on the original compound are still in progress, and thus the validity of the Rivaroxaban patents remains a focus of dispute. One of the parties in the patent infringement litigation, Nanjing Chia Tai Tianqing Pharmaceutical Company (“Petitioner”), filed an invalidation request against the patent in question in December 2019.

Issues:

The Petitioner brought up issues of sufficiency/enablement, clarity of scope, priority, and inventive step in the invalidation request. However, the case focused on the issue of inventive step, interpreting how to apply CNIPA’s examination standards on inventiveness in the field of chemical compounds.

Analysis:

The Panel emphasized how the three-step approach is applied particularly in the field of chemical compounds:

- searching for the closest prior art and identifying the closest “starting point” compound;

- analyzing the structural difference(s) between the claimed compound and the closest prior art compound; and

- determining the actual technical problem solved based on the use and/or effect achieved by the structural difference(s).

Once the actual technical problem is identified, determine whether a skilled person in the art has a technical inspiration to solve said problem based on the prior art and common knowledge.

Decision:

Bayer’s patent was upheld as valid on the basis of amended claims submitted by the patentee during the invalidation proceedings (Decision No. 45997).

Detailed Case Study

The Petitioner, Nanjing Zhengda Tianqing Pharmaceutical Company (“Petitioner”), argued that the patent was invalid for failing to comply with Article 26, paragraphs 3 (sufficiency/ enablement), Article 26, paragraph 4 (clarity of scope), and Article 22, paragraph 3 (inventiveness) of the Chinese Patent Law. Additionally, they argued the patent did not have valid priority.

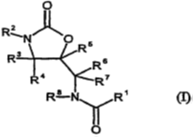

Below is originally granted claim 1 of the granted patent:

1. A compound or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt, hydrate, or salt hydrate thereof of general formula (I):

wherein

R1 is a 2-thienyl group which is substituted at the 5- position by a group selected from chlorine, bromine, methyl or trifluoromethyl,

R2 is -DA-

wherein A is phenylene;

D is a saturated 5- or 6- membered heterocyclic ring connected to A via a nitrogen atom, having a carbonyl group in the ortho position from the attached nitrogen atom; and wherein one of the ring carbon units can be replaced by a heteroatom selected from S, N or O;

A can be optionally substituted by one or two groups selected from the group consisting of fluorine, chlorine, nitro, amino, and trifluoromethyl, methyl and cyano at the meta position from the point of attachment to the oxazolidinone; and

R3, R4, R5, R6, R7, and R8 are hydrogen.

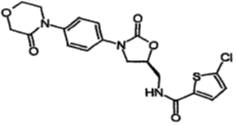

After exchanging numerous pieces of evidence, counterevidence and arguments, the parties proceeded onto oral hearings with an amended claim set based on originally granted claim 2 but deleted the technical solution corresponding to “salt hydrate”. This claim essentially recited the drug molecule itself, Rivaroxaban. The amended claim 1 read as:

1. A compound or a pharmaceutically acceptable salt or hydrate thereof, the compound having the structure of the follow formula:

Sufficient Disclosure

According to Article 26.3 of the Patent Law, “[t]he description shall set forth the invention or utility model in a manner sufficiently clear and complete so as to enable a person skilled in the relevant field of technology to carry it out.”

What’s in the Specification?

The patent provides novel anticoagulants which unexpectedly strongly and selectively inhibit Factor Xa. The specification discloses how to test for Factor Xa inhibition, Table 1 discloses the anti-inflammatory effects of the compounds after oral and IV administration in rat models, Thrombotic activity, (including oral ED50 data for the claimed compound in Example 44), and compound preparation methods and analytical data (e.g.,. HNMR, HPLC) confirming those compounds. Notably, an IC50 of 0.7nM of the claimed compound (Example 44) is also disclosed, but it does not clearly state against what target.

Petitioner’s Argument

The Petitioner argues that the patent has insufficient disclosure because it is not clear that the IC50 values shown in the patent specification relate to inhibition activity against Factor Xa (except Example 17). Although the specification provides ED50 values for Factor Xa by oral route, the experimental methods for measuring ED50 are not described.

Panel Conclusion

After taking a look at the amount of data in the specification, the Panel concluded that a skilled person in the art would be convinced that the claimed compound was effective at inhibiting Factor Xa and could be used orally. Other data, such as the ED50 in the rat models, together with the overall teachings of the specification, gave sufficient evidence that the claimed compound could be used orally and had good Xa inhibitory activity. The lack of details teaching how to calculate ED50 was not fatal, since it was well known in the art what ED50 means and how to obtain it in these well-established rat models. Accordingly, the claims are sufficient under Article 26.3 of the Patent Law.

Clarity of Scope

According to Article 26.4 of the Patent Law, “the claims shall be supported by the description and shall define the extent of the patent protection sought for in a clear and concise manner.” Importantly, a skilled person in the art should reasonably expect that all the technical solutions outlined in the claims can solve the technical problems and achieve expected technical effects over the entire scope of the claims.

The Petitioner’s Argument

The Petitioner argued that the “hydrate” in the claim was not supported by the specification because it is unpredictable whether the hydrate exists, and if it exists, in what form.

Panel’s Response

The Panel disagreed, pointing to the specification which provided general teaching about the concept of hydrates and how they work with pharmaceutical compounds, which is the same as in the art. Notably, after the claimed compound undergoes oral dissolution, the hydrate actually appears as the compound itself. According to the general knowledge in the art, a hydrate’s efficacy will be the same as the compound’s efficacy. The burden of proof falls on the Petitioner to show otherwise.

Priority

The standard for priority in China is whether a technical solution can be “directly and undoubtedly derived from the earlier application.”

The Petitioner’s Argument

The Petitioner argued that the patent could not validly claim priority to its priority document. More specifically, the Petitioner argued that the compound of amended claim 1 was not disclosed in the priority document.

The Patentee’s Argument

The patentee countered by arguing that priority should be based on when an inventive concept was first disclosed, not a specific compound.

Panel’s Response

The Panel sided with the Petitioner, reasoning that Markush groups typically have a broad and diverse set of possible structures, not a simple combination of finite choices. Accordingly, a particular undisclosed species that falls within the scope of a broader genus would not be entitled to the earliest priority date.

As a result, three additional prior art documents (Evidence 5, 7 and 13) that published after the priority date could be used in the inventive step analysis.

Inventive Step

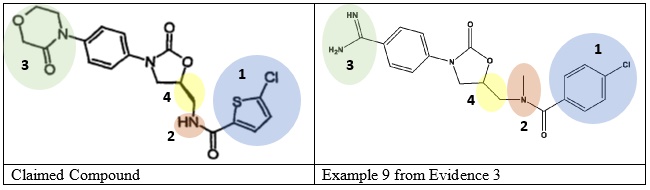

The Petitioner argued that the claimed invention does not possess inventive step in view of Example 9 in Evidence 3 (shown below) as the closest prior art. They asserted that Example 9 solves the same technical problem, and combined with additional prior art documents (Evidence 4-13), renders the claimed invention obvious.

Differences Between the Prior Art and Claimed Invention

The Petitioner pointed out four differences between the claimed compound and the prior art:

- 5-chlorothiophen-2-yl vs. 4-chlorophenyl (indigo)

- NH vs. NCH3 amide (orange)

- 3-oxomorpholin-4-yl vs. formamidinyl (green)

- S isomer vs. unknown (yellow)

The prior art discloses that benzamidine derivatives inhibit Factor Xa, but does not provide any experimental data.

Petitioner’s Arguments

The Petitioner introduced several additional prior art documents that taught the molecular shape of the biological target’s “pocket”; explained how to modify the structures to improve certain PK or PD properties; and provided suggestions for using certain functional groups at certain positions for inhibiting Factor Xa. The Petitioner argued that Evidence 4 taught how the benzamidine functional group bound to the S1 pocket of the receptor, and Evidence 4 also provided examples of non-benzamidines that were more similar in structure to the claimed compound. Evidence 5 taught that the two ends of the Factor Xa inhibitor could be replaced with morpholino phenyl. Additional prior art references describing the binding pocket taught the advantages of making the S4 binding region become non-planar (e.g., substitution on the N-site of the morpholinyl ring resulting in both steric hinderance and preventing the morpholinyl and the phenyl from being in the same plane).

The Panel’s Response

The Panel disagreed with the Petitioner’s logic. The Panel argued that the closest prior art taught that benzamidine derivatives were effective for inhibiting Factor Xa (as opposed to a non-amidine structure, such as oxomorpholino). All the examples were benzamidines, and even the title of the document was “Benzamidine Derivatives”. Accordingly, a skilled person in the art would use Example 9 as a starting point to modify the main structure. Based on the disclosure of Evidence 3, the skilled person would not be motivated to replace such an essential functional group. Furthermore, there is no teaching in Evidence 3 on how to modify the core phenyloxazolidinylamine structure.

Additionally, most of the additional prior art references (Evidence 4-9) also only disclosed benzamidine compounds.

Even considering that Evidence 4 included non-benzamidine examples, it also does not teach how to modify the core phenyloxazolidinylamine structure, and specifically provides no teaching on how to insert the morpholinyl group into the core of Evidence 3.

Similarly, the Petitioner argued that Evidence 3 taught that that multiple group substitutions were possible at a particular position, and Evidence 5 taught 5-chlorothiophen-2-yl group as one such possible group. The Panel disagreed, noting that Evidence 5 and the claimed invention had different core structures, and it was not obvious that two such different core structures would be interchangeable.

The Panel emphasized that the chemical arts was an experimental science. When modifying compounds, the first step is to find the sites that need to be modified. The second step is to choose replacement groups based on any technical inspiration from performance properties of the groups or other structures in the field, not merely to combine together a simple patchwork of individual groups from compounds with different main structures in the prior art. Even though replacement of small molecule substituents in the field of medicinal chemistry is conventional in one sense, the multiple modifications needed to arrive at the presently claimed compound required inventive step. A skilled person would not easily arrive at the claimed invention based on routine work without technical inspiration for how to modify the specific structure based on the teachings from the prior art.

As such, the claimed invention is inventive and all claims were upheld.

Concluding Thoughts

We believe this case was chosen as a “Top 10” Patent Re-examination and Invalidation case because of the significance of the drug at issue, from its medical impact to the world to its large market size. We are quite encouraged by the level of depth involved in the analysis. The Panel has considered carefully the unpredictability of the chemical arts, the wealth of data demonstrating Rivaroxaban’s superior attributes, and even carefully considered very technical arguments relating to the 3D structures of the binding pocket.

It would have been interesting to see whether the originally granted claim would have stood up to the invalidation. Although the prior art may not have taught the oxo-morpholinyl (and related) structures of the original broader claim, it is likely that Bayer knew it would have a significantly stronger case if it could submit the plethora of experimental data that it had on Rivaroxaban, despite the risk of not being able to claim priority.

This case brings qualified good news to pharmaceutical companies. At a minimum, it shows that patents directed towards an approved drug (which presumably have a boatload of associated efficacy data) are quite strong and should stand up to invalidation in China. It is yet another example of a “Western” patent being upheld while challenged by a domestic company. At the same time, it brings a nagging sense of doubt for broader granted claims that, on their face, look like they should be upheld, but for one reason or another, ended up not making it into the final set of litigated claims.

Will future drug companies take the same approach, choosing to voluntarily limit their own claims during an invalidation in order to ensure that they win? One strategy to avoid this problem would be to pursue two (or even more) separate patents in China, one directed towards the exact drug and other directed towards the genus. This way, patentees can avoid the difficult decision that Bayer had to make in trying to choose the most “successful” path forward.

About the Authors

Jennifer Che, J.D. is Vice President and Principal at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

Pauli Wong is a Chinese Patent Attorney at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice or a legal opinion on a specific set of facts.