Recently, all eyes have been on China as the fundamental patent covering semaglutide, the active ingredient in Ozempic® and Wegovy®, will expire on March 20, 2026. It goes without saying that generics are ramping up bigtime in China (and also around the world), preparing to manufacture and sell this blockbuster drug to one of the biggest markets in the world. Any shortening of the patent term for this key semaglutide patent in China could cause an immediately shift in the Chinese Ozempic market (not to mention directly impacting Novo Nordisk).

Novo Nordisk’s Semaglutide Patent in China

On September 5, 2022, the China National Intellectual Property Association (China’s patent administrative office, hereinafter “CNIPA”) declared Novo Nordisk’s key semaglutide patent in China1 to be invalid.2

The petitioner was Hangzhou Zhongmei Huadong Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (“Huadong”), a Chinese drug manufacturer that currently already sells a generic version of liraglutide, another GLP-1 receptor agonist originally developed by Novo Nordisk. The CNIPA indicated that Novo Nordisk’s patent disclosure did not contain any actual experimental data, making it difficult to confirm that all the compounds possessed the surprising technical effects asserted in the specification.

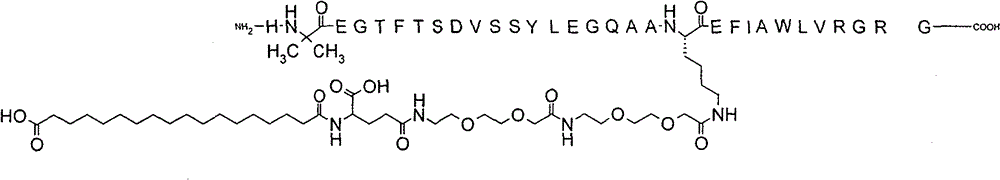

The amended claims at issue3 claimed a single compound (semaglutide), compositions comprising the compound, and preparations of a medicament comprising the compound for treating a variety of different medical conditions (e.g., hyperglycemia, diabetes, IBD, etc.).

Translation of amended claim 1 (which refers to semaglutide)

- A compound, wherein said compound is

N-ε26-[2-(2-[2-(2-[2-(2-(2-[4-(17-carboxyheptadecanoylamino)-4(S)-carboxybutanoylamino]ethoxy)ethoxy]acetylamino)ethoxy]ethoxy]ethoxy)acetyl][Aib8, Arg34]GLP-1-(7-37) peptide.

Novo Nordisk submitted significant evidence in the form of post-filing experimental data showing that semaglutide had increased half-life and a longer duration of action when compared with liraglutide, the closest prior art.

Nevertheless, despite the amended claim scope and post-filing data, the panel of 3 judges concluded that the patent was entirely invalid. The data itself was compelling and showed improvement over the closest prior art (liraglutide). However, the CNIPA argued that the technical effect about the longer duration of action “could not be obtained from the specification as originally filed.”

Novo Nordisk appealed to the Beijing IP Court, which reversed the CNIPA’s invalidation and upheld the patent.

In order to fully understand the nuance of the Beijing IP Court’s decision and rationale, we provide first a brief “primer” about post-filing data in the patent world.

Post-Filing Supplemental Data: why this is such a hot topic

One of the biggest concerns amongst life science patent attorneys with regards to China has been post-filing data; more specifically, about China’s lack of flexibility in accepting it. In general, China is notoriously strict about experimental data requirements in patents, especially in fields that are “unpredictable”, such as biology, chemistry, and the like. Patent applicants typically can only obtain a scope of protection tightly around aspects of their invention that they have “proven” through working examples.

Contrast this to other jurisdictions, like the US and Europe, which usually allow broader scopes of protection based on less number of working examples. Furthermore, jurisdictions like the US and Europe are more lenient when it comes to allowing patent applicants to rely on data generated after the patent filing to help support a broader claim scope after-the-fact. As a result of this difference, most patentees get much narrower patents in China compared to the US and Europe, at least in “unpredictable” fields such as the life sciences.

In 2021 the United States and China signed Phase One of the US China Economic and Trade Agreement. Under this agreement4, China agreed to update its patent laws to “permit pharmaceutical patent applicants to rely on supplemental data to satisfy relevant requirements for patentability, including sufficiency of disclosure and inventive step.”

While China had been accepting post-filing data under certain circumstances prior to 2021, in the 2021 Examination Guidelines, China further solidified the instructions for Examiners to consider post-filing supplemental data. Specifically, Part 2 Chapter 10 Section 3.5.1 of the current Examination Guidelines stipulates that Examiners shall consider post-filing supplemental data

- when considering inventive step5 and sufficiency6

- if the technical effect demonstrated by the supplemental data could undoubtedly be obtained by a skilled person in the art from the disclosure as originally filed.

The Examination guidelines provided several helpful examples to demonstrate how Examiners should treat post-filing data (we’ve written a more extensive article about these examples in this blog post).

Novo Nordisk’s Post-Filing Data

As we saw from above, Novo Nordisk had mountains of data on semaglutide, most of it probably generated after the original patent application was filed. The Beijing IP Court had to decide whether to accept this data. The key question centered upon: what is the standard for “could undoubtedly be obtained by a skilled person in the art from the disclosure as originally filed”?

What was in the Disclosure as Originally Filed?

The patent disclosure described a genus of compounds that were effective as GLP-1 receptor agonists. Notably, there were 22 actual example compounds that were described specifically with their preparation methods and characterization data, including semaglutide. The patent disclosure described screening studies using db/db mice and minipigs. However, it did not specify which GLP-1 compound(s) were used in these screening studies.

Semaglutide Patent in China Rejected for Lack of Inventive Step

During the invalidation, all claims were rejected for lack of inventive step (Article 22.3), in view of the closest prior art, liraglutide. Although the two compounds were not identical, they shared a lot of common molecular structures. The CNIPA argued that one of skill in the art would expect that semaglutide would behave similarly to liraglutide, given their similar structure and their similar mechanisms of action.

Nova Nordisk argued that semaglutide had surprising technical effects that were markedly improved over liraglutide, pointing to post-filing comparison data showing semaglutide’s significantly improved half-life (60-70 hours in minipigs) and long duration of action (48 hours in db/db mice) compared to liraglutide (24 hours).

As the original specification did not specify which compoundspossessed the above-mentioned surprising effects, (and thus no mention of semaglutide specifically having such technical effects), the CNIPA opined that the effects demonstrated by the supplemental data “could not be undoubtedly obtained by a skilled person in the art from the disclosure as originally filed”.

The Beijing IP Court’s Reasoning

Long Duration of Action

However, the Beijing IP Court sided with Novo Nordisk, agreeing that the patent disclosure as originally filed did possess sufficient support for the idea that semaglutide had a long duration of action. Specifically, the Beijing IP Court pointed to paragraph [0534] in the specification, which stated:

[0534] In one aspect of the invention, the GLP-1 agonist has a duration of action of at least 24 hours after administration to db/db mice at a dose of 30 nmol/kg.”

According to the Beijing IP Court, the statement “the GLP-1 agonist” was referring to the entire genus of compounds, and thus was asserting that all the compounds (or at least the 22 examples in the specification) had a duration of action at least 24 hours after administration. The Beijing IP Court judge wrote in a follow up statement about this case, “[a]lthough this technical effect is not specifically described as a technical effect of semaglutide, it can be reasonably inferred that semaglutide has this technical effect since it is a specific compound within the scope of protection of the general formula compound.”

In essence, the general statement in paragraph [0534] was strong enough that the technical effect demonstrated by the supplemental data (duration of action after 24 hours) could undoubtedly be obtained by a skilled person in the art. The court emphasized that if a patentee has already demonstrated that a general formula has a particular effect, then it can be presumed that all the compounds within the general formula have this effect. In this case, the patentee should have the right to submit post-filing data to confirm the effects of a specific compound within the general formula. Otherwise, if this was not allowed, the patentee would need to recite the results of each specific compound in the original specification, which would not be reasonable nor practical.

Prolonged Half Life

The Beijing IP Court contrasted the above case to the other study using minipigs on prolonged plasma half-life. Below is an English translation of two other paragraphs from the specification (emphasis added):

[0543] One aspect of the present invention is the preparation of GLP-1 analogues/derivatives with prolonged plasma half-life suitable for weekly administration. Pharmacokinetic properties can be assessed in minipigs, or domestic pigs as described below.

[0550] A second part of the pharmacokinetic screening was conducted on those compounds with an initial terminal half-life of 60-70 hours or more. This screening consisted of a single dose intravenous and subcutaneous administration of 2 nmol/kg to six minipigs for each route of administration. […]

The Beijing IP Court argued that in the study using minipigs, the specification did not clearly indicate which GLP-1 analogs have the technical effect of having a longer half-life. Instead, the property of having “an initial terminal half-life of 60-70 hours or more” was recited as the conditions required for a second screening rather than recited as technical effects in paragraph [0550]. The judges argued that, based on the conditions stated in paragraph [0550], one of skill the art would not be able to infer that semaglutide could be suitable for the second part of the screening, and there was no way for one of skill in the art to know undoubtedly that semaglutide would possess the technical effects of having a half-life of 60-70 hours or more. As a result, the post-filing supplemental data regarding increased half-life was not accepted by the court.

Since Novo Nordisk only needed to demonstrate that semaglutide had improved properties over liraglutide with respect to one aspect (duration of action > 24 hours), the patent was upheld based on the admissibility of the post-filing data.

Eagle IP Thoughts: semaglutide patent in China

This is a HUGE case for so many reasons. The sheer importance of the product, the economic and legal impact of the decision, and the fine line the Court ultimately drew to clarify China’s position on post-filing supplemental data make this a fascinating case to study.

At a minimum, this case broadens the standard for what types of statements in a specification could be sufficient to demonstrate that an idea can be “undoubtedly obtained” from the disclosure as filed. Importantly, in this case semaglutide was never specifically called out as having significantly good PK properties. Instead, the specification held a general position that the compounds (implicitly all the compounds) had a >24 hour duration of action.

Drafting Strategies

For patent practitioners, the ability to have this additional “hook” based on generic language could be a lifesaver in a lot of situations. Astute patent drafters should consider carefully what types of general statements asserting technical effect they wish to add. A general statement that’s not entirely true (and unsupported by data) could be fatal, while a general statement that is true could literally save the life of a patent (as it did in this case). Be careful making statements that imply only a subset of compounds have a certain technical effect (unless it’s true and supported by data).

To hedge against future inventive step challenges, consider adding “hooks” describing as many different and unique properties of a lead molecule as possible. For example, one could add physical properties, PK properties, efficacy data in various models, and more. For any of these unique features that may help distinguish the to-be-patented product from the prior art, try to provide at least one method of testing that feature. It’s hard to know what type of data is needed to overcome unexpected prior art. Having the “hooks” makes it much easier to submit post-filing data to demonstrate inventiveness over the cited reference.

What If . . .

It begs the question, though. What would happen if Huadong were able to show that some of the compounds in the group of 22 examples did not have such property? Would that negate the statement entirely? In the case above, would the other compounds showing negative results negate the general statement, and thus remove the support for the surprising effects of semaglutide? Would the court still accept semaglutide’s good post-filing data in this case?

This case isn’t completely over yet. Huadong has appealed to the Supreme People’s IP Court. March 20, 2026 is still two years away, but we expected to hear a final decision before the patent expiration date. As always, we are watching this case closely and will report updates as soon as we hear more.

If you would like to have more information on this matter or would like to have our advice, please feel free to contact us at eip@eipgroup.asia.

About Eagle IP

Eagle IP is a top-tier boutique patent firm with a unique mix of experienced US and Chinese patent professionals with significant cross-border knowledge and experience. Our technically expertise covers wide range of technologies including, but not limited, to life sciences, biotechnology, medicine, pharmaceuticals, material and environmental science, chemistry and consumer electronics. We have years of experiences in drafting and prosecuting patent applications involving biological deposits, sequence listings, small and large molecules, drug discovery and development, material science, software and engineering, and many others.

This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice or a legal opinion on a specific set of facts.

About the Authors

Jennifer Che, J.D. is President & Managing Director and a US Patent Attorney at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong and Shenzhen.

Audrey Cheung is a qualified Chinese Patent Attorney at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong and Shenzhen.

Yolanda Wang is a Principal, Chinese Patent Attorney, and Chinese Patent Litigator at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong and Shenzhen.

ZL 200680006674.6

↩︎Invalidation Decision No. 57950

↩︎Based on the amended claims from an earlier invalidation case brought by Hangzhou Jiuyuan Gene Engineering Co., Ltd and decided on 8 Apr 2022, which were ruled to be partially invalid by the CNIPA.

↩︎Article 1.10: Consideration of Supplemental Data

1. China shall permit pharmaceutical patent applicants to rely on supplemental data to satisfy relevant requirements for patentability, including sufficiency of disclosure and inventive step, during patent examination proceedings, patent review proceedings, and judicial proceedings.

↩︎Article 22.3 of the Chinese Patent Law: Inventiveness means that, as compared with the prior art, the invention has prominent substantive features and represents an obvious progress, and that the utility model has substantive features and represents a progress.

↩︎Article 26.3 of the Chinese Patent Law: The description shall contain a clear and comprehensive description of the invention or utility model so as to enable a person skilled in the relevant field of technology to carry it out; where necessary, drawings shall be attached to it. The abstract shall state briefly the main technical points of the invention or utility model.

↩︎