This is Part III of a three-part series summarizing the Examination Guidelines that were released by the CNIPA on January 15, 2021, one year to the date of Phase 1 of the US and China Economic and Trade Agreement.

That agreement included specific provisions where China “shall permit pharmaceutical patent applicants to rely on supplemental data to satisfy relevant requirements for patentability, including sufficiency of disclosure and inventive step . . .” (Article 1.10).

Furthermore, these new Guidelines also introduce a more rigorous approach to inventive step (to avoid Examiner hindsight!) for chemical and biological inventions, including a number of helpful examples.

Part I of this series covered examples on post-filing supplemental data. Part II explored examples on novelty and inventive step for chemical /compounds inventions. Today’s Part III will explore examples on inventive step for biological inventions.

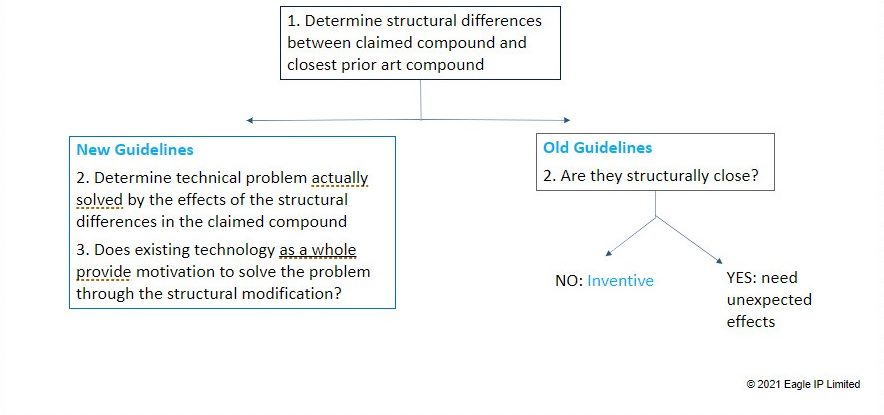

Inventive Step: Problem Solution Approach

The new Examination Guidelines have tightened the analysis that Examiners must make when making an inventive step determination.

After determining the structural differences between the closest prior art compound and the claimed compound, Examiners must then a) determine the technical problem solved by the effects of the structural differences in the claimed compound and b) determine whether the existing technology as a whole provides motivation to solve the problem through structural modification.

Now, unlike in the past where an Examiner could just (based on hindsight) determine that two structures were “similar” and issue a rejection, the Examiner has the burden to show how the existing technology provides motivation for the change. We have discussed this issue at length in Part II of this 3-part series.

With respect to biological inventions, the Guidelines further emphasize that inventions in the field of biotechnology involve different types of subject matter, such as macromolecules, cells, and individual microorganisms. In addition to using structure and composition, these inventions can be characterized in other ways, such as by the deposit number of a biological material. As such, examiners must take into account and balance structural differences, distance of a genetic relationship, and predictability of technical effect when evaluating inventive step for a biotechnology invention.

The Examination Guidelines provide several examples that help examiners consider whether two biological structures would be similar or not. Part II of this series covered chemical compound inventions. Part III below covers biological inventions.

Monoclonal Antibodies

The Guidelines re-affirm that monoclonal antibodies can be defined by structural features (e.g., sequence listing) or by the hybridoma that produces it, such as by way of submitting a deposit with the China General Microbiological Culture Collection Center (CGMCC). Example claims are shown below:

Claim 1. A monoclonal antibody against antigen A, comprising VHCDR1, VHCDR2, and VHCDR3 having amino acid sequences as shown in SEQ ID NO: 1-3, and VLCDR1, VLCDR2, and VLCDR3 having amino acid sequences as shown in SEQ ID NO: 4-6.

Claim 2. Monoclonal antibodies against antigen A produced by hybridomas with deposit number CGMCC NO:xxx.

With respect to inventive step, if an antigen is known, the monoclonal antibody is still considered inventive if it has

- A different sequence in the key areas that determine function and use

- Different or improved performance and

- There exists no teaching in the prior art.

Genes

Similar to the above example for monoclonal antibodies, a new gene is inventive if the protein encoded by the gene has

1. A different amino acid sequence;

2. Different or improved performance; and

3. No teaching in the prior art.

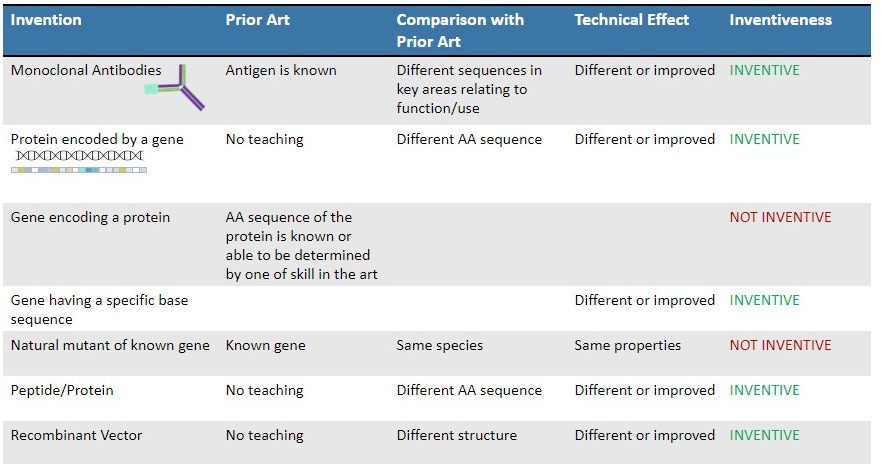

Peptides, Proteins, Recombinant Vectors

The Guidelines provide additional examples showing different types of prior art, technical effect, and differences between the prior art and the claimed invention. As can be seen from the summary chart below, in almost all examples, inventions with unexpected technical effects are inventive. On the other hand, if a gene or an amino acid sequence of a protein is already known, related aspects (e.g., mutants of the gene or the gene encoding the protein) will not in themselves be inventive absent unexpected technical effects.

General Thoughts

All in all we are quite encouraged by this set of Examination Guidelines. We think clarifying the problem solution approach is really important and will be very helpful in ensuring that examiners don’t rely too much on hindsight when making an inventive step rejection. However, it remains to be seen how much teeth the requirement to show “motivation” really has when the level of skill of the Chinese “skilled practitioner” is so much higher than that of the US “ordinary skilled person”.

We also appreciate Example 1 in the Sufficiency section, which very clearly provides an example where NO DATA was presented in the specification as filed, but where an examiner still needs to consider post-filing supplemental data. However, we note that the standard of “undoubtedly deduce” is still quite high, and it will take time for us to understand where that line actually exists in the biotech and chemical arts.

In general we find the examples surrounding Inventive Step to be more or less in line with current CNIPA practice. However, it’s still helpful to have real “official” examples, which at least create consistency in Chinese examination practice. Furthermore, if applicants encounter examiners who are not following the proper procedures, they can point to these examples as well as to the revised problem solution approach (discussed in Part I of this Series) when rebutting inventive step rejections by examiners who have not made a proper prima facie case.

All Posts in This Series: CHina’s Newest Examination Guidelines

Part I: Post-Filing Supplemental Data for Compounds

Part II: Novelty and Inventive Step for Compounds

Part III: Inventive Step for Biological / Life Science Inventions

This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice or a legal opinion on a specific set of facts.

About the Authors

Jennifer Che, J.D. is Vice President and Principal at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

Yolanda Wang is a Principal, Chinese Patent Attorney, and Chinese Patent Litigator at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

Sally Yu is a Chinese Patent Attorney at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.