Each year The Intellectual Property Tribunal of the Supreme People’s Court releases a list of top 10 technical intellectual property rights court case decisions. The 2020 list came out a few months ago, and we have been highlighting some of these cases.

Today, we will cover a utility model patent infringement case. As one of the three types of patents one can obtain in China (the other two being invention patents and design patents), utility models are popular due to their reduced costs and relative ease of prosecution (no substantive examination). Some might argue that a utility model patent has limited value, having restricted subject matter eligibility, a shorter term, and lower patentability requirements. Because they are not substantively examined, many “garbage patents” are granted, and then often subsequently invalidated once they are challenged.

As a result, utility model patents do not command the same level of respect or “awe” in people’s minds. Additionally, this also causes infringers to blatantly ignore the consequences of infringement, thinking that these patents have little enforceability or “teeth”.

Interestingly, the case we’re going to discuss today demonstrates that a utility model can be quite powerful, and especially if the market is big enough, it can provide significant returns on investment and play an important part in a strategic global patent strategy. At the same time, infringement of utility model patents can also bring serious consequences to the infringer.

CASE DETAILS

Case number | (2020) SPC IP Civil Final 357 |

Decision day | July 24, 2020 |

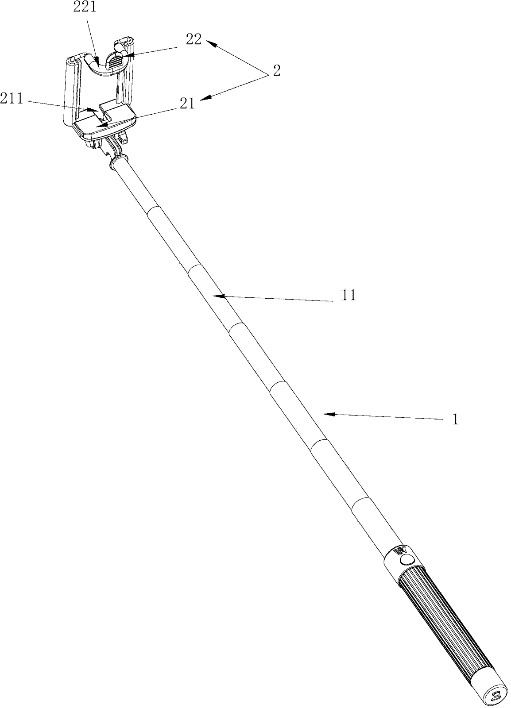

Patent Title | Integrated self-photography apparatus |

Patent involved | ZL201420522729.0 (‘729) |

| Litigant | Appellant (Defendant in the original trial): Zhongshan Pinchuang Plastic Products Co. Ltd. Appellee (Plaintiff in the original trial): Winners’ Sun Plastic Electronics (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd. |

| Court of the first instance |

|

Court of the second instance |

|

Legal issue | The People’s Court applies Article 65 of the Patent Law for statutory compensation, consideration of the infringement and the circumstances of the infringement |

Legal basis | 《中华人民共和国专利法》(以下简称专利法 2010)第十一条第一款、第六十五条,《中华人民共和国民事诉讼法》第一百七十条第一款第一项。(Article 11 Paragraph 1 and Article 65 of the Patent Law of the People’s Republic of China (henceforth referred to as the Patent Law 2010), Article 170 Paragraph 1 of the Civil Procedure Law of the People’s Republic of China.) |

Winners’ Sun Plastic Electronics (Shenzhen) Co., Ltd. (henceforth referred to as Winners’ Sun) is the patentee of a utility model titled Integrated Self-Photographing Apparatus. Winner’s Sun’s core business is selfie sticks, and it has grown that core business to 400 million within seven years. Winners’ Sun has been using this single, award-winning[1] utility model patent to file a massive number of lawsuits against manufacturers and sellers nationwide (China) to protect its patent right.

This particular case is between Winners’ Sun and Zhongshan Pinchuang Plastic Products Co. Ltd (henceforth referred to as Pinchuang). Winners’ Sun sued Pinchuang for patent infringement, arguing that Pinchuang was manufacturing infringing selfie sticks, affixing different company’s logos onto the selfie sticks, and then selling the selfie sticks.

The Guangzhou Intellectual Property Court (“Guangzhou IP Court”) affirmed that Pinchuang was the manufacturer of the infringing products. After considering (1) the infringing nature of the source of manufacturing and (2) Pinchuang’s intentional and repeated infringement activities, the Court ordered Pinchuang to cease infringing activities and compensate Winner’s Sun 1 million RMB.

Dissatisfied with the verdict, Pinchuang appealed to the Supreme People’s Court (SPC). Pinchuang has no objection to the fact that the product infringed the patent ‘729.

The main disputes of this case are

- Whether Pinchuang implemented the act of manufacturing the alleged infringing product

- Whether the compensation amount is unreasonable

The first dispute: Whether Pinchuang manufactured the alleged infringing product

Pinchuang argued that it did not implement the act of manufacturing the alleged infringing product. However, Winners’ Sun provided a notarized video showing Pinchuang’s production of the alleged infringing products. Pinchuang countered that the evidence was just an old promotional video they recorded before, and did not prove that any new manufacturing activities. The court disagreed, concluding there was new infringing activities because the new infringing products were different from the one litigated in a previous case between the parties (No. 495). The product from the previous case No. 495 had a “JJi” trademark, whereas the current accused infringing products did not have the trademark. In addition, there was only one infringing product in the previous case No. 495, while this case involved four different infringing products. The court found this evidence persuasive, noting that Pinchuang’s deliberate and repeated infringements have seriously infringed Winner’s Sun’s patent rights. The court further concluded that Pinchuang had bad faith or intent in repeatedly infringing the Winners’ Sun patent.

The second dispute: Compensation amount

The significance of this case mainly lies in the calculation of damages. Because Winners’ Sun failed to provide evidence to prove specific amounts in statutory damages, infringer’s profits, or evidence of royalties, the court must determine damage compensation on a discretionary basis based on the nature of the alleged infringement and the infringing product. The court will consider factors such as the value and profit rate of the infringer, the operation status of the accused infringer, the subjective malice of the accused infringer, and the compensation to the right holder in related cases.

Manufacturers like Pinchuang, who printed different logos onto the infringing products based on its customers’ requests, caused many infringing products to flow to multiple market channels. In fact, the court noted that Winners’ Sun did indeed file a large number of patent infringement lawsuits all over the country, with most of the accused infringers being retailers and sole proprietorships.

Hence, patentees like Winners’ Sun face increased difficulties and costs protecting and enforcing their patent rights. Manufacturers act as the original source of this infringement; therefore, courts should intensify penalties for this type of infringement. Likewise, patentees like Winners’ Sun should focus their patent litigation efforts on the original source of the infringing activity, namely the manufacturer in this case.

Decision:

The SPC held in favor of Winners’ Sun, handing it yet another legal victory. Despite repeated invalidation attacks, Winners’ Sun’s utility model patent continues to hold strong and still remains valid. The SPC also ruled that Pinchuang sold and manufactured the alleged infringing product, and therefore is the source of the IP infringement. The court concluded that Pinchuang willfully infringed the patents, continuing to manufacture and sell the products even after defending two civil infringement lawsuits for breach of the same patents involved. The court further judged that this action, combined with similar cases for several other infringing products, reached the threshold demonstrating Pinchuang’s deliberate intent to violate the patent right in this case. The court found Pinchuang’s activities to be a case of serious infringement. The court also held that the statutory compensation amount should be determined from a higher level within the range prescribed by law. As a result, the appeal was rejected and the original verdict was upheld.

Further Analysis

We believe this case was chosen as a “Top 10” case because it demonstrates the importance of tracing back to the source of the infringing activity (in this case, the manufacturing process); and provides a real-world example of how enforcing a utility model patent provides real value in China. For example, as of today, there have been 2,295 completed lawsuits for this patent. Winners’ Sun has successfully obtained compensation in most of the cases, receiving an average of tens of thousands of yuan in compensation. It’s amazing to consider that this single utility model patent will likely provide compensation amounts of up to 100 million yuan. It’s encouraging to see China’s commitment to strengthening IP judicial protection, and as a result, how Chinese innovator companies are quickly learning how to use the system to defend their innovations.

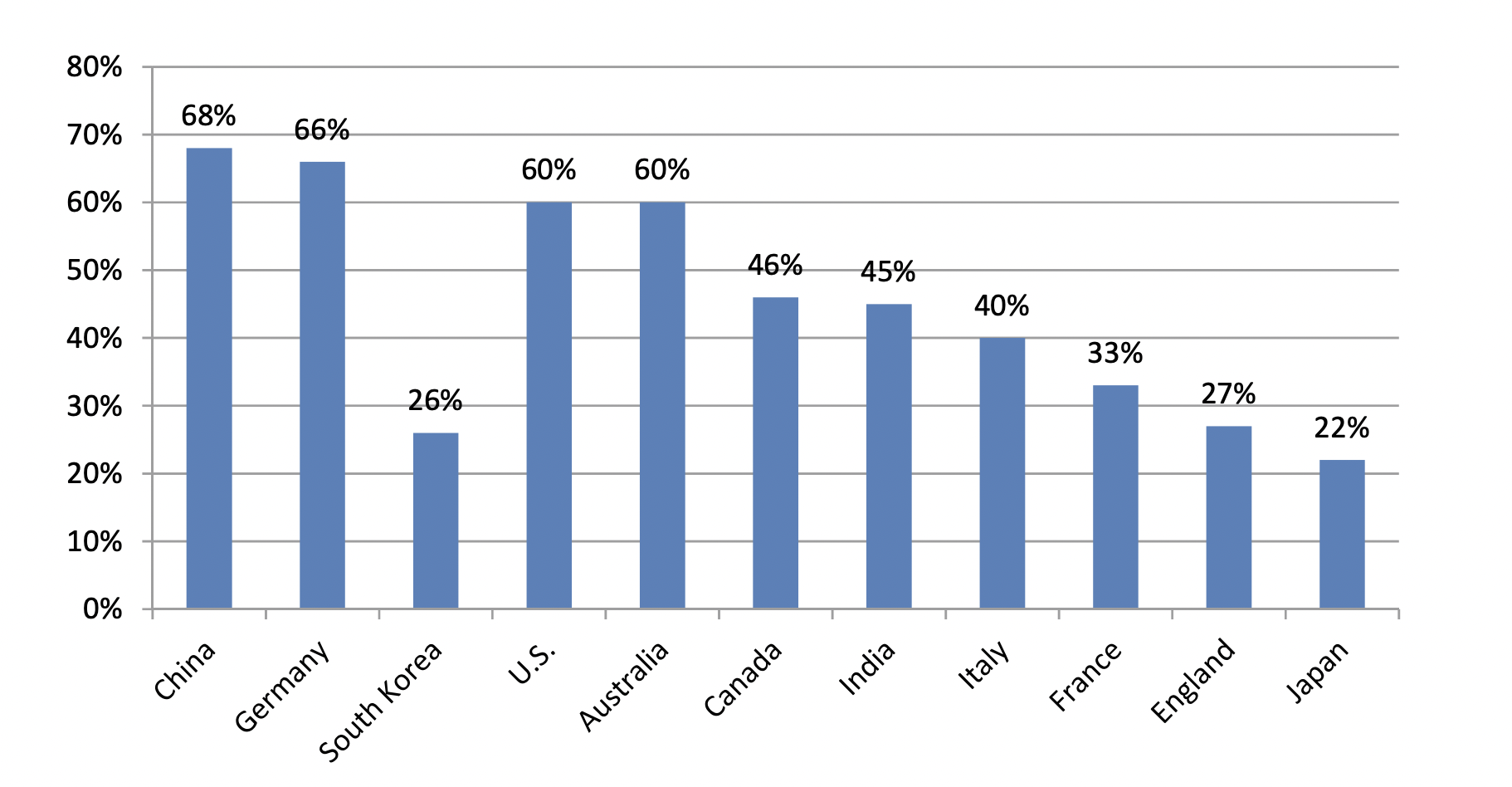

According to the Global IP Project (2014), China is one of the fastest-growing jurisdictions for patent litigation worldwide. An international comparison of patent litigation success rates in infringement cases and validity cases conducted by Global IP Project (2014) shows that IP rights holders in China enjoy a higher success rate than in other countries (see Figs. 1.1 to 1.3)

Fig 1.1 Patent owner infringement win rates in first instance litigation (2006-2012)

Source: Global IP Project (2014)

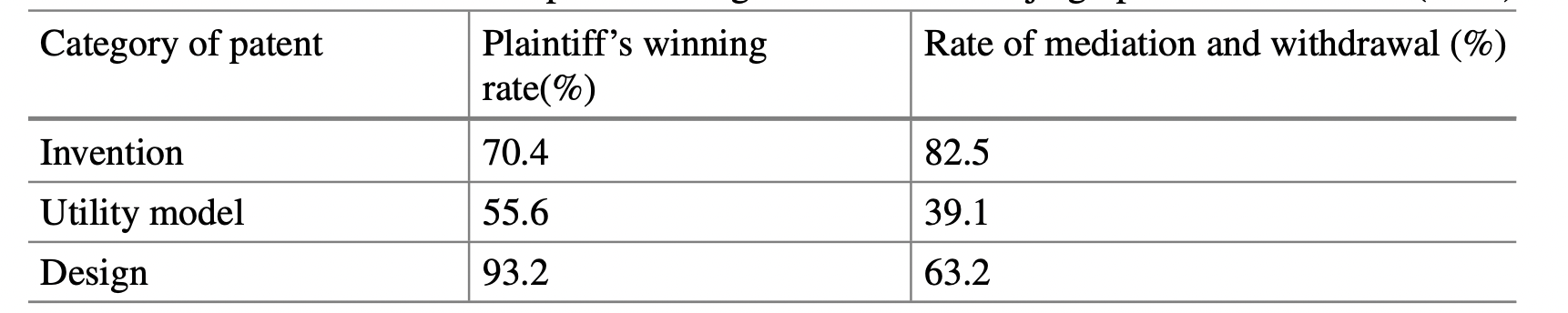

Fig 1.2 Plaintiff’s win rate in patent infringement cases at Beijing Specialized IP Court (2016)

Source: Beijing IP Court Report

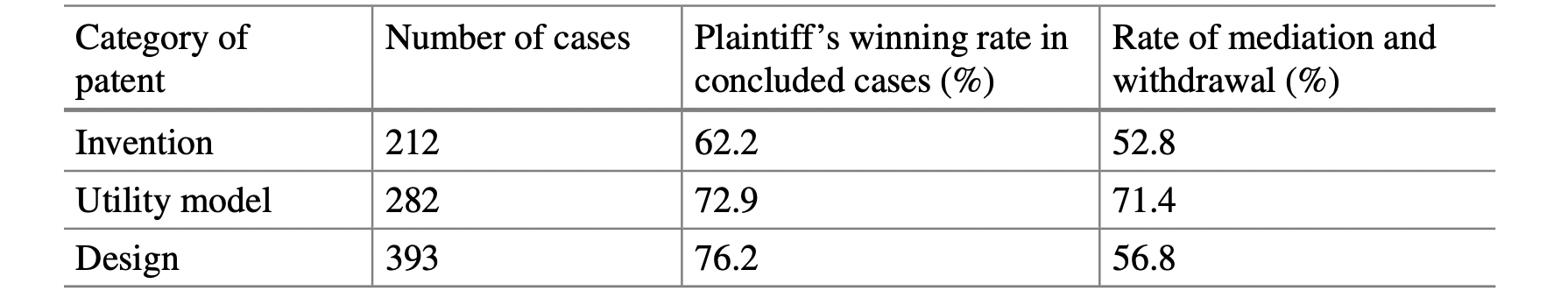

Fig 1.3 Plaintiff’s win rate in patent infringement cases at Shanghai Specialized IP Court (2015-2016)

Source: Shanghai Specialized IP Court Report

The average success rate in countries with bifurcated IP infringement adjudication systems is 49% compared to 39% in countries with unified IP infringement adjudication systems. In China, the patentee litigation success rate between 2007 and 2013 was 72% for utility model patents (381/531).

This case study demonstrates how utility model patents can play an important part of a larger international patent strategy. Because the standard for inventiveness is lower for a utility model, these patents are usually easier to obtain and harder to invalidate. Despite their shorter patent life (only 10 years), they still prevent free-loading by competitors in market segments dominated by inventions with limited levels of inventiveness, which are particularly prevalent in developing economies. Additionally, utility models, which are granted much more quickly, can serve as valuable assets in order to help start-ups raise capital more quickly.

Winners’ Sun built up a strong patent portfolio related to the selfie stick, including winning the 20th China Patent Gold Award for the litigated UM. According to Incopat, Winner’s Sun overall patent portfolio consists of 60+ patents all around the world. Utility models, often overlooked, can surprisingly provide a cost-effective addition to a larger international patent portfolio strategy. It is perfect for products with limited inventiveness and/or a short commercial life. It can also be useful in a dual-filling strategy, where two concurrent patent applications (an invention and a utility model) are filed at the same time. Because a utility model does not undergo substantive examination, it will typically grant much earlier than an invention patent. An earlier granted utility model can provide interim protection until the invention patent grants, or if it never grants, can provide alternate protection in lieu of an invention patent.

It seems pretty clear that innovators worldwide should at least consider utility model protection, especially for products that have a shorter commercial life, need patent protection as soon as possible, have innovations that are less “inventive”, or have a limited budget. The’ 729 patent, which does not seem “high-tech” has resisted up to 19 invalidation requests, and claims 2-13 are still valid thus far. This case clearly demonstrates that even such a “petty” patent can reap rewards in the hundreds of millions of RMB, which is not really a petty amount anymore.

Source:

- Prud’homme, D. 2017. Utility model patent “strength” and technological development: Experiences of China and other East Asian latecomers. China Economic Review 42: 50–73.

- Moga, T. 2012. China’s utility model patent system: Innovation driver or deterrent. US Chamber of Commerce Publications.

- Prud’homme, D. 2017a. Utility model patent “strength” and technological development: Experiences of China and other East Asian latecomers. China Economic Review 42:50–73.

- https://zhuanlijiang.com/plus/view.php?aid=298

- Chinese Patent CN203797307U

- 20th China Patent Gold Award ↑

About the Authors

Clara Tan is a senior at Tsinghua University and an intern at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

Jennifer Che, J.D. is Vice President and Principal at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice or a legal opinion on a specific set of facts.

One Comment

Pingback: