China has been implementing a plethora of new laws and measures that are particularly favorable to drug companies, such as patent term extension and patent linkage. Details of the new implementation measures for patent linkage (technically “early dispute resolution mechanisms for drug patents”) came into effect on July 4, 2021. At around the same time, China’s public registration system for innovator companies to list patent associated with marketed drugs (China’s version of the US FDA’s “Orange Book”) began accepting registrations.

It has been close to one year since these mechanisms were put in place. The first legal decisions from these patent challenges are now coming out, and the first appeal was just decided by the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) last month (August 2022).

Some Background: China’s Patent Linkage System

China’s patent linkage mechanism is similar to the US version. Generic small molecule drug applicants applying for marketing approval must “certify” the patent status of the marketed drug they are seeking to sell by making one of four statements and providing supporting evidence. The first two statements essentially indicate that there are no active patents that will block the generic drug. The third statement says the generic drug applicant will wait until the listed patent is expired (before marketing its generic drug). Only the fourth statement “[t]he generic drug applicant believes the listed patent should be invalid (4.1 declaration) or not infringed (4.2 declaration)” requires some sort of patent challenge, such as a patent invalidation or a non-infringement opinion issued by an IP Court or patent office, (“patent linkage dispute”).

As soon as this mechanism became available in 2021, pharmaceutical companies around the world began listing their marketed products on China’s public registration system. Soon after, generics began to challenge these patents.

IP Court Rules Against Chugai Pharma

We previously published an article summarizing the initial decisions (both at the CNIPA and at the Beijing IP Court (BJIPC) for these maiden generic drug challenges in China. On April 15, 2022, the first instance BJIPC ruled that the generic product of Eldecalcitol, a drug for osteoporosis produced by Wenzhou Haihe Pharmaceutical Industry (Haihe), did not fall within the scope of the innovator, Chugai Pharmaceutical (Chugai)’s patent.

Below are the first two claims of the granted patent:

1. A composition comprising:

(1) (5Z, 7E)-(1R, 2R, 3R)-2-(3-hydroxyl propoxyl)-9,10-secocholesta-5,7,10 (19)-triolefins-1,3,25-triol;

(2) lipids; and

(3) an antioxidant;

wherein, the antioxidant is added to prevent

(5Z, 7E)-(1R, 2R, 3R)-2-(3-hydroxyl propoxy)-9,10-cholesterol-5,7,10 (19)-triolefins-1,3, 25-triol

from being degraded to

6E-(1R, 2R, 3R)-2-(3-hydroxyl propoxy)-9,10-cholesterol-5 (10), 6,8 (9)-triolefins-1,3, 25-triol

and/or

(5E, 7E)-(1R, 2R, 3R)-2-(3-hydroxyl propoxy)-9,10-cholesterol-5,7,10 (19)-triolefins-1,3, 25-triol;

wherein after 12 months, the amount of

6E-(1R, 2R, 3R)-2-(3-hydroxyl propoxy)-9,10-cholesterol-5 (10), 6,8 (9)-triolefins-1,3, 25-triol

and/or

(5E, 7E)-(1R, 2R, 3R)-2-(3-hydroxyl propoxy)-9,10-cholesterol-5,7,10 (19)-triolefins-1,3, 25-triol

is 1% or less.

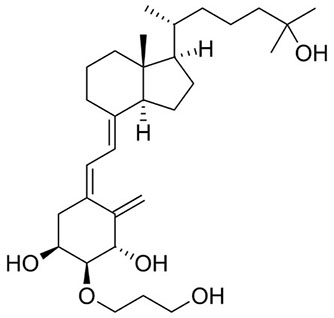

2. The composition according to claim 1, wherein the antioxidant is one member selected from dl-α-tocopherol, dibutylhydroxytoluene, butylhydroxyanisole, and propyl gallate.

In a Separate Invalidation Challenge

During a separate invalidation challenge, Chugai amended the scope of claim 1 to narrow the antioxidant towards a single antioxidant “dl-α-tocopherol” and cancelled claim 2.

Based on court documents published recently, it appears that Haihe’s generic product included an antioxidant *** (redacted due to confidentiality reasons), which was one of the antioxidants listed in the original specification of Chugai’s patent. However, because the granted claims had been amended in a separate invalidation challenge to only be directed to dl-α-tocopherol, the resulting claim no longer covered antioxidant ***.

As such, the BJIPC ruled that Haihe’s generic drug did not fall within the scope of Chugai’s patents.

Chugai appealed the judgment at the Supreme People’s Court (SPC).

Chugai Appeals: China’s First Ever Patent Linkage Appeal

SUMMARY: The appeal was rejected and the SPC affirmed that Haihe’s generic drug did not fall within the scope of Chugai’s patent.

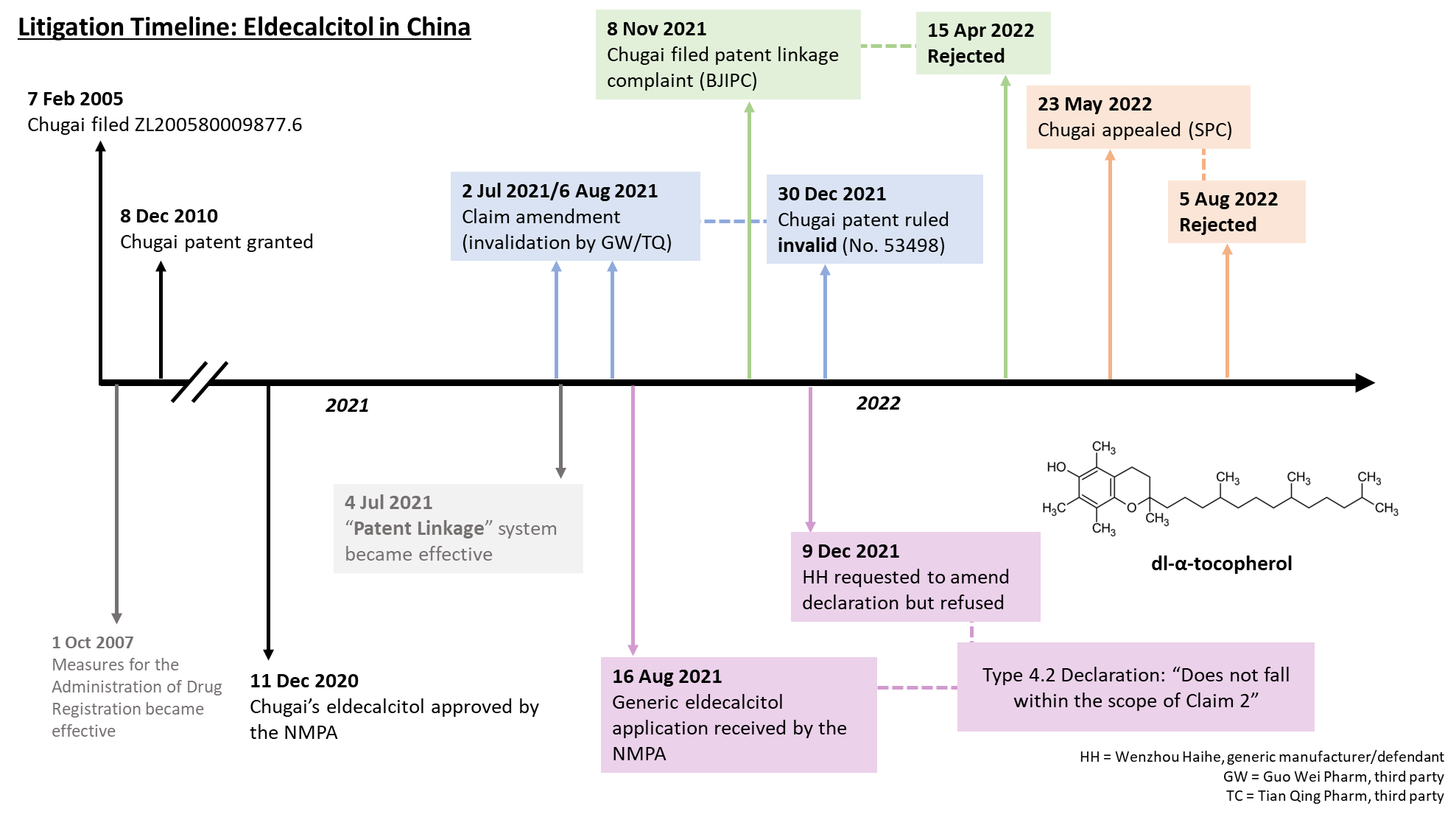

The relevant timeline of the Chugai/Haihe case is shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. A summary of the Chugai/Haihe case.

The SPC focused on the three main issues below:

- Whether Haihe had violated NMPA (National Medical Products Administration, a Chinese regulatory agency) regulations

- Which antioxidant was involved in the generic drug application

- Whether *** and dl-α-tocopherol were equivalent

Below is a summary of the SPC’s opinion:

(1) Whether Haihe had violated NMPA regulations

The patent linkage system requires a generic drug applicant to file a declaration certifying the status of each relevant patent of the listed innovator drug. The relevant rules[1] do not explicitly state that the declaration must be directed towards specific claims of the relevant patent. Since the purpose of a 4.2 declaration is to disclaim the generic drug from the protection scopes of the innovator drug patents, it would make more sense to disclaim the generic drug from the broadest claim scopes, i.e. the broadest independent claims.

Haihe’s Unusual Declaration:

Haihe’s stated in their declaration that their generic drug did not fall within the scope of dependent claim 2, directed towards certain antioxidants in Chugai’s patent[2]. Interesting, they did not make such a declaration for claim 1, the broadest claim. Additionally, claim 2 was subsequently removed during invalidation proceedings[3] just prior to Haihe’s application and registration of generic eldecalcitol. The claim amendment didn’t publish until after the NMPA received Haihe’s generic drug application. Only after Chugai filed the instant patent linkage complaint did Haihe request to amend their declaration.

The SPC criticized Haihe’s behavior of avoiding the broadest claim in the 4.2 declaration as being improper and unjustified. However, in view of the fact that original claim 2 was actually broader than the scope of independent claim 1 after amendment,[4] as well as the fact that the patent linkage regulations are still on a test run at this stage, the improper declaration did not ultimately spose any substantive disadvantageous effect in this case.

In addition, the patent linkage system requires the generic drug applicant to

- notify the market authorization holder of the innovator drug;

- provide a comparison between the technical scheme and the relevant claims; and

- provide a comparison to relevant technical data.

The SPC further criticized Haihe for not notifying Chugai nor providing the relevant comparisons to Chugai until the instant complaint had been filed (especially since Chugai’s contact information was available on the drug registry platform). Despite Haihe’s improper actions, there were no actual consequences imposed on Haihe.

(2) Which antioxidant was involved in the generic drug application

The NMPA will grant market authorization based on a generic drug applicant’s drug application documents (“generic application documents”) and (if relevant), the results of any patent linkage dispute. Therefore, it only makes sense to use the generic application documents to determine (1) the features of the generic drug, and (2) whether the generic drug falls within the scope of the patent.

If the actual generic drug being made or the manufacturing process used are inconsistent with the technical details provided in the generic application documents, the generic drug applicant will bear legal liability in accordance with the regulations established by the NMPA.

If the innovator patentee believes that the actual generic drug being made or the generic drug’s manufacturing process fall within the innovator’s patent protection scope, the innovator should file a separate civil complaint for infringement.

However, is it the SPC’s job to determine whether this type of infringement is occurring?

Chugai’s Request to Investigate Haihe’s Actual Activities for Infringement:

In the appeal, Chugai requested two reports of investigation evidence from the SPC. The first one was to obtain the eldecalcitol capsules manufactured for clinical trial purposes from Haihe. Chugai argued that *** (the antioxidant used in the generic drug) was commonly known as being part of a genus of antioxidants comprising dl-α-tocopherol, yet dl-α-tocopherol was the only legally approved antioxidant of the *** genus. They believed that Haihe only replaced dl-α-tocopherol with *** in the application documents just to get away from the patent linkage requirement, and investigating these capsules could prove whether dl-α-tocopherol was actually involved in the manufacture of generic eldecalcitol.

The second request was to order all application documents submitted by Haihe regarding the antioxidant *** from the NMPA, which were not limited to the ones provided in the first instance court.

The SPC’s Response:

The SPC reviewed all the evidence from the first instance court, and confirmed the following:

- *** had been recited in all application documents submitted to the NMPA;

- the name, formula and chemical structure of *** was not the same as dl-α-tocopherol; and

- *** was a species of antioxidant.

The SPC reiterated that the legality of stating the use of *** in the application documents would be up to NMPA’s investigation, and it would not affect the SPC’s judgement, which would be solely based on what was disclosed in the application documents. The SPC would only determine whether the generic product (as described in the application documents) infringed the patent. They would not determine whether the product described in the application documents was actually the product being manufactured, used in the clinical trial, and sold. That should be addressed in a separate civil complaint for infringement.

Therefore, the SPC rejected Chugai’s requests for investigation evidence.

(3) Whether *** and dl-α-tocopherol were equivalent

From the analysis in (1) and (2), the SPC had determined that Haihe’s application documents submitted to the NMPA would be the most appropriate subject of comparison, meaning that the technical solution involving the use of *** as the antioxidant should be compared to the patent scope in a doctrine of equivalents analysis.

According to Article 6 of the Interpretation of Patent Infringement Disputes,

if the applicant or patentee has given up part of its claim scope during an invalidation proceeding, the SPC does not allow the recapturing of the surrendered subject matter in infringement disputes, unless the patentee can provide evidence explaining that the subject matter has not been surrendered.

In other words, amendments made during an invalidation proceeding give rise to an estoppel that limits the use of the doctrine of equivalent in an infringement dispute.

As discussed above, Chugai had removed the broader claim scope of multiple antioxidants and narrowed the scope to only include dl-α-tocopherol during the invalidation proceedings. In the SPC’s point of view, Chugai had surrendered the other antioxidants, including ***, in their attempt to survive an invalidation, and they were not able to provide evidence showing the contrary. Therefore, the use of *** cannot be included in the instant analysis, and the technical solution provided by the use of *** is not equivalent to dl-α-tocopherol. The SPC thus concluded that Haihe’s technical scheme for generic eldecalcitol did not fall within the protection scope of Chugai’s patent and the original judgement from the BJIPC upheld.

Some Thoughts:

Balance Between Patent and Regulatory Agencies

It is interesting to note the delicate balance between decisions at the SPC and the NMPA. For example, even if Haihe did not comply with NMPA regulations (and “switched out” the antioxidant to a version that is “not FDA approved”), the SPC refused to comment on the overall legality of the situation, but only focused their judgment on whether Haihe’s product as described in the application documents infringed Chugai’s patents. NMPA, after all, oversees regulatory matters, and is best situated to determine whether the marketing approval application is legitimate (e.g., if the product described in the application papers is different from the product either used during clinical trial, or worse yet, used on the market). This case at least puts innovator companies on notice, cautioning them to be aware of potential tricks that generic drug companies can use during this early period when the rules are still being tested.

Doctrine of Equivalents / Estoppel

In this case, we were not able to see how the SPC would have judged the DOE issue without prosecution history estoppel. Here, Chugai’s options were quite limited because during a patent invalidation in China, a patentee can only delete claims or amend claims to incorporate limitations having support in the granted claims, not from the specification as a whole. As such, if indeed original claim 1 was invalid for lack of novelty or inventive step, Chugai’s options for amendments were quite limited, and (for whatever reason), Chugai chose to amend claim 1 all the way down to one specific antioxidant. Perhaps they thought that the NMPA would not approve a generic drug that switched out a component from the original product.

In any event, this decision hurt Chugai a lot, allowing Haihe to copy one of Chugai’s other claimed antioxidants in their generic formulation, and also get around the post-invalidation amended claims.

This begs the question: if there were no estoppel issues, how would the SPC consider the doctrine of equivalents with respect to the 4.2 declarations? Would the analysis be the same as a typical infringement or invalidation request? If Chugai had not amended the claims during prosecution to narrow away from those other antioxidants, but had merely pursued a very narrow claim in a divisional, would they have had a chance to argue for equivalence?

More worrying, will the NMPA approve Haihe’s generic product if it is clearly different from Chugai’s marketed product? Will the NMPA go on that investigative fact-finding mission to determine whether Haihe actually conducted its clinical trials with an infringing product or with the product using the alternate *** antioxidant?

We are certainly in interesting times as China is laying down the groundwork for its own patent linkage path. The first few “guinea pigs” of this system are certainly feeling some of the initial pains as certain holes in the system get exposed.

For example, we can probably be certain that going forward, every single innovator company will at least scrutinize whether generic drug companies are properly making declarations for all independent claims of a patent. Future generic companies may not get as much leniency if they fail to notify innovator companies or if they aren’t forthright in their declarations.

Patentees should also be much more wary of the potential for prosecution history estoppel arising from claim amendments made during invalidation. Perhaps more creative divisional strategies should be considered for pursuing certain narrow scopes first so as to prevent any prosecution history estoppel from happening for certain important claim scopes.

On a positive note, innovator companies should still be able to file a civil complaint for infringement if generic companies like Haihe actually conduct a secret “switch” and begin selling products on the market that use the original antioxidant (and thus infringe the granted patent).

All eyes are surely on the NMPA to see how it handles the approval of Haihe’s product in this situation. Whatever happens will speak loudly to the international pharma industry as it tries to figure out how friendly China’s patent linkage system will be.

We look forward to learning more as additional decisions come down the line.

This article is for general informational purposes only and should not be considered legal advice or a legal opinion on a specific set of facts.

https://www.nmpa.gov.cn/directory/web/nmpa/images/1625323300528019998.doc ↑

Original claim 2: “The preparation according to claims 1, wherein the antioxidant is one member selected from dl-α-tocopherol, dibutylhydroxytoluene, butylhydroxyanisole, and propyl gallate.” ↑

In the SPC judgment document, it was revealed that in 2021, two requests of invalidation against the Chugai patent were filed by Guo Wei and Tian Qing (two third-party generic drug manufacturers). Chugai resorted to amendment the claims in their eldecalcitol patent as they were challenged by these third parties that the support for Claim 2, a dependent claim directing to a group of antioxidants, was not sufficient. As a result, the original claim 2 was removed in the amended claims submitted on 2 Jul 2021 and 6 Aug 2021 (claim amendments were the same), and dl-α-tocopherol was added to claim 1 as the only antioxidant. ↑

- Amended claim 1: “1. A preparation, […] (3) antioxidant: the antioxidant is dl-α-tocopherol. […]” ↑

About the Authors

Jennifer Che, J.D. is Vice President, Principal, and a US Patent Attorney at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

Audrey Cheung is a Patent Technology Specialist at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

Yolanda Wang is a Principal, Chinese Patent Attorney, and Chinese Patent Litigator at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.