Learning from a 2019 China’s Top 50 Representative IP Case

The number of patent applications in China is now the highest in the world, with more than half the applications filed as utility model applications (UMs). For example, there were more than 2 million UMs filed in 2018 alone (for the difference between a utility model and an invention patent in China, see here). However, less than 1% are filed by foreigners[1]. This reflects the lack of appreciation on the part of many foreign companies of what protection UMs can confer, and there is a general misunderstanding that UMs are by definition poor in quality. This misconception is fueled by the poor performance of infringement litigation of some UMs, as the non-infringing case below illustrates. However, although the quality of UMs are far more variable than invention patent applications, if used properly, UMs can add tremendous value to any patent portfolio.

Background

Shenzhen Laidian Technology Co., Ltd (“Laidian”), who owned a UM entitled “Absorption charging device[2]”, sued Shenzhen Jiedian Technology Co., Ltd (“Jiedian”) and Hunan Oceanwing E-commerce Co., Ltd (“Oceanwing”) for infringement in 2017[3]. Jiedian’s shared chargers, the alleged infringing product in this dispute, is extremely popular and widely used in China, installed in over 70 cities, with 3.44 million shared chargers in many places including subway stations and hospitals.

The first court decision ruled that Jiedian’s shared chargers fell within the scope of claims 1, 7, 8, 9 and 10 of Laidian’s patent. Jiedian was thus ordered to cease infringement and compensate Laidian for 1 million RMB. In 2018, after claims 1 – 3, 5 – 8 were invalidated by Jiedian, the Beijing High People’s Court ruled on appeal that the alleged infringing product still fell within claims 9 and 10, thus the first court decision was maintained.

The Final Decision: Supreme People’s Court

Jiedian appealed to the Supreme People’s Court (SPC) arguing that the lower courts erred in finding infringement. The main issue to resolve was whether Jiedian’s alleged infringing product fell within the scope of invalidated claim 1. The rationale was that if the product did not infringe on claim 1, then infringement of valid claims 9 & 10 becomes moot.

The dispute narrowed in on whether the infringing product contained the technical feature “transmission component” in the patent.

Claim 1:

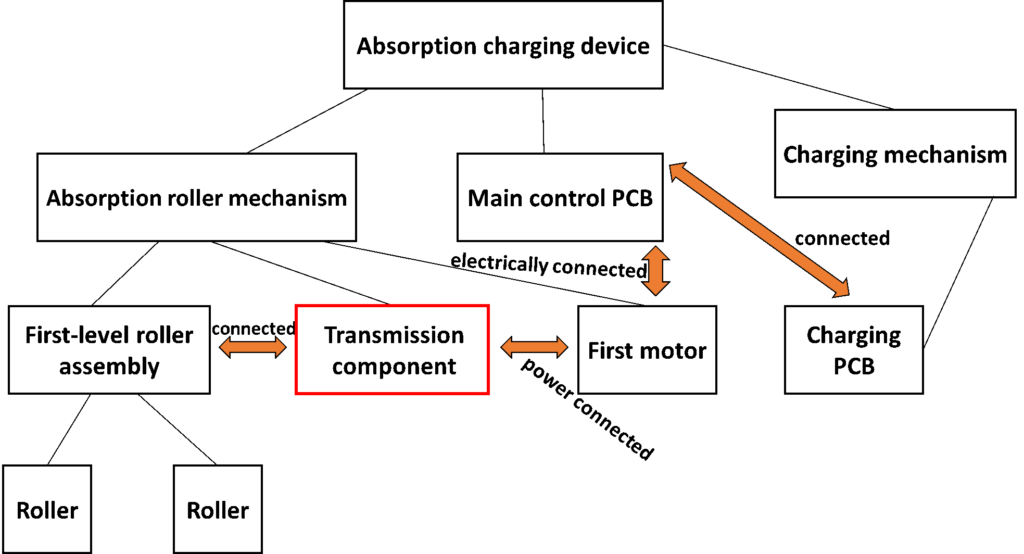

1. An absorption charging device, characterized in that it includes an absorption roller mechanism, a charging mechanism, and a main control PCB; the absorption roller mechanism includes a first motor connected to and drives a transmission component, and a first-level roller assembly connected to the transmission component; the first-level roller assembly includes two opposite rollers; the first motor is electrically connected to the main control PCB; the charging mechanism includes a charging PCB connected to the main control PCB.

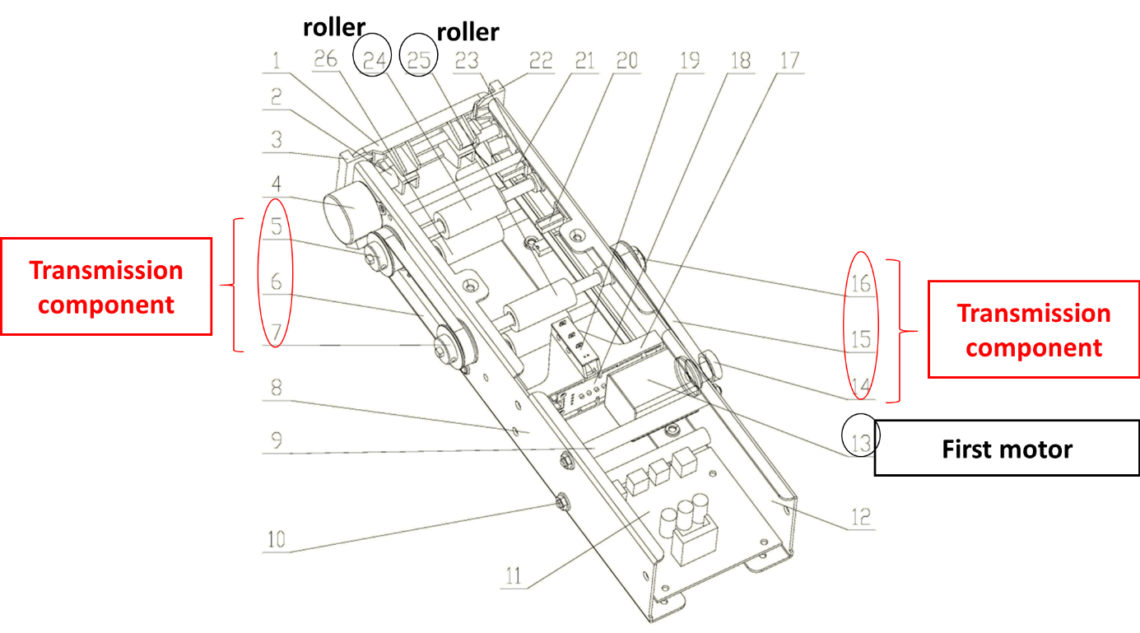

Figure 1 below shows the various components and their connections with each other as indicated in claim 1. The red box indicates the “transmission component”, the focus of the dispute.

Based on prior Supreme Court Interpretations[4] and the claim language itself[5], the Court concluded that the “transmission component” should be understood as the combination of one or more components that transmit(s) power from the first motor to the first-level roller assembly.

Furthermore, the “transmission component” should be recognized as functional feature since this term is not a general technical term in the field[6]. When looking at claims that use functional language to describe technical features, the Court should look to the specification/drawings to determine what are features and their equivalents[7]. In this case, the “transmission component” should include the belt pulley, gear drive, etc., and their equivalents, according to the specification and drawings of Laidian’s patent.

The Key Term: “transmission component”

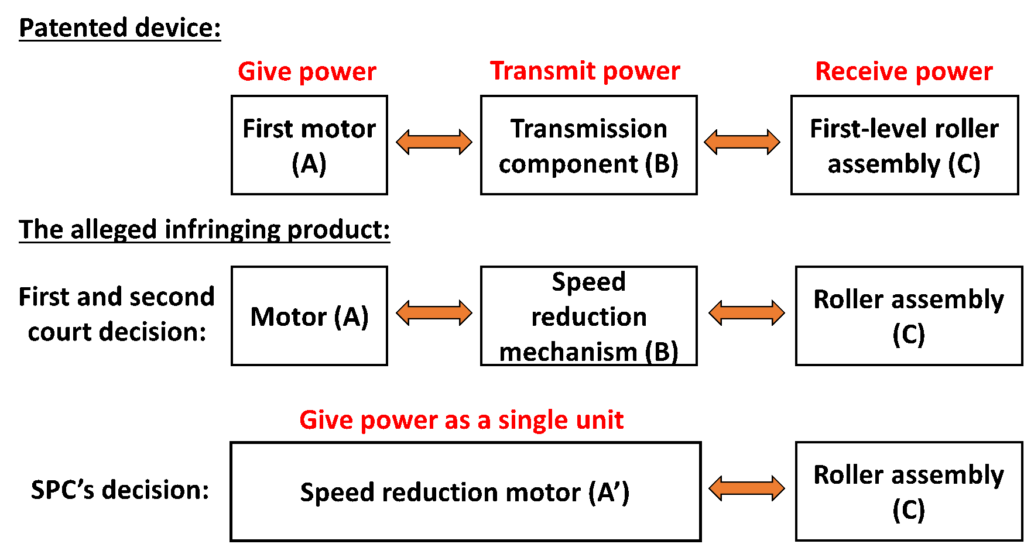

The key question is whether the alleged infringing product included this “transmission component.” With respect to the alleged infringing product, the second court decision determined that the speed reduction motor thereof is composed of the motor (see A of Figure 3) and the speed reduction mechanism (see B of Figure 3), the function of which is to achieve power transmission and reduce power output. Please see Figure 3 for illustration.

In the second court decision, the speed reduction mechanism (B) of the speed reduction motor in the alleged infringing product was determined to be the “transmission component”.

The Supreme People’s Court

However, the SPC disagreed. They pointed out that when classifying the technical features of the claims, generally speaking, a technical unit that can perform a relatively independent technical function should be regarded as one technical feature, and it is not appropriate to define multiple technical units that perform different technical functions as one technical feature. The “transmission component” in claim 1 is independent of the motor and is not a component of the motor. Its function is to transmit the force of the motor to the roller, so that the motor can be packaged in the mechanical structure and in the meantime drive the roller.

Since the speed reduction motor (A’) is an integrated motor that integrates the motor and the speed reduction mechanism, those skilled in the art would generally consider the speed reduction motor (A’) as a whole i.e. a single unit. As part of the speed reduction motor (A’), the main function of the speed reduction mechanism is to reduce the power output. As the speed reduction motor (A’) of the alleged infringing product is directly connected to the roller assembly (C), the power transmission is performed by direct connection. No “transmission component” (B) was thus found in the Jiedian’s product.

As a result, Jiedian’s product was found to be outside the scope of the claim 1. Since both claims 9 and 10 depend on claim 1 (and are thus narrower), Jiedian’s product also did not fall within the scope of claims 9 or 10. The Supreme People’s Court thus withdrew the first and the second court decisions.

What Lessons Can We Learn?

From a basic level, we can learn about how Laidian’s narrow claim drafting strategy hurt them in the end. Because they drafted claims by literally describing every feature in their product, they failed to consider embodiments where a single element could perform two functions that were performed by two different elements in their invention.

In this case, the lack of substantive examination for UMs was not the cause of the defect. This is because it is not the job of an examiner to determine the commercial value (or lack of it) of a claim in respect of its breadth. Substantive examination (if this UM were to be filed as an invention patent application instead) could only have caused further narrowing of any claims. Thus claims that were already narrow and specific when originally drafted would have remained so, or become even narrower during prosecution.

In fact, a good claim drafting strategy would have provided broader claims as alternatively, and allowed the patentee to retain various permutations and options to pursue the best coverage. This would include creatively working with inventors to brainstorm “design–around” embodiments for the invention, and then claiming those embodiments. If such an exercise had been done, perhaps the inventors would have thought of embodiments such as a speed reduction motor – which is very commonly used in the field – or other implementations that could serve as a basis for more generalized feature(s) in the claims. UMs can indeed provide excellent protection if the right strategy is employed.

[1] https://www.wipo.int/ipstats/en/statistics/country_profile/profile.jsp?code=CN

[2] “Absorption charging device” (ZL201520103318.2)

[3] (2019) Supreme Law No. 348

[4] Article 2 of the “Interpretation of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Patent Infringement Dispute Cases”

[5] “the absorption roller mechanism includes a first motor connected to and drives a transmission component, and a first-level roller assembly connected to the transmission component”

[6] Article 8 of “Interpretation (II) of the Supreme People’s Court on Several Issues concerning the Application of Law in the Trial of Patent Infringement Dispute Cases”

[7] Article 4 of “Several Provisions of the Supreme People’s Court on Issues Concerning Applicable Laws to the Trial of Patent Controversies”

About the Authors

Bill Yip is a Patent Scientist at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

Dr. Jacqueline Lui is Founder and President of Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.

Jennifer Che, J.D. is Vice President and Principal at Eagle IP, a Boutique Patent Firm with offices in Hong Kong, Shenzhen, and Macau.